|

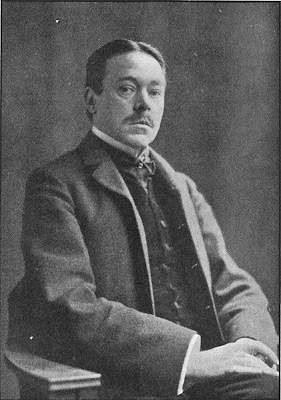

| Wilhelm Voigt at his arrest (source: Wikipedia) |

In October, 1906, Wilhelm Voigt, aged 57, was down on his luck. He'd

first been convicted of theft at age 14, and had since then managed a

rather impressive career of thievery and forgery. In February of 1906,

he'd been released after a 15 year long sentence for having broken into

the building of the Court of Justice at Wongrowitz, in Posen, and stolen

the money box. It would later be noted by the judicial authorities that

the sentence had been "excessively heavy and to have been imposed after

a somewhat irregular trial."[1]

According to the accounts that were later given of his prison time,

Voigt had been an exemplary prisoner who had shown great interest in

reading, especially history, and apparently upon release, he had

expressed a desire to live an honest life. He finally settled down

outside of Berlin to work as a shoemaker. His employer, aware of his

antecedants, later testified that "Voigt had rewarded his confidence,

and had led an honest and most industrious life, and had made himself

useful in a variety of ways. He had regularly attended church, had eaten

his meals with the family of his employer, and had been kind to the

children." [2] However, as a former prisoner he was an "undesirable",

and on those grounds he was expelled from Berlin by the police.

According to his employer, "[w]hen the order for his expulsion came,

Voigt had utterly broken down and had felt that his last chance of

leading an honest life."

But apparently Herr Voigt decided not to take this lying down. No,

instead he planned and executed a caper which would resonate across the

known world. First, he visited several used-clothes stores and managed

to piece together a uniform of an officer of the 1st Foot Guards. Thus

equipped, he was ready to execute his

coup.

His exact intentions may be disputed – he would later himself claim that

"it had not been his original intention to rob the municipal treasury,

that what he had chiefly desired to secure was a pass which would have

enabled him to earn an honest living" [3] but that might obviously not

have reflected the truth. Undisputed, however, is the fact that on 16

October, 1906 he commandeered all in all 11 soldiers from the local

garrison and travelled with them by train to Köpenick, where he led them

into the town hall. He then placed the local Burgomaster, Dr.

Langerhans, and his treasurer under arrest for charges of crooked book

keeping. He told the local police to care for law and order and to

prevent calls to Berlin for one hour at the local post office. Then he

ordered the treasurer to hand over the money box, containing 4,002

Marks. Frau Langerhans, the wife of the Burgomaster, would later state

to the press that "it was the extreme politeness of the 'captain'

towards herself and his official gruffness towards her husband which

chiefly convinced her that he was a real officer." [4]

He then told some of the soldiers to take the arrested men to Berlin for

interrogation in two commandeered carriages and left the remaining

guards under orders to stay in

their places for half an hour. Himself, he left for the train station

and disappeared.

The incident caused great mirth and excitement. Only a few days after the incident

The Times

could report that in Berlin "(t)he

music-halls are already giving representations of the whole drama,

illustrated postcards with descriptive verses are being sold in

thousands in the streets, and the schoolboys have invented a new game

which they call 'Der Hauptmann von Köpenick' and in which they re-enact

the comedy in all its details." [5] As the National-Zeitung reported

"(i)mmeasurable laughter convulses Berlin and is spreading beyond the

confines of our city, beyond the frontiers of Germany, beyond the ocean.

The inhabited world is laughing, and if we still had an Olympus, the

gods would undoubtedly be laughing too". [6]

But there was more to the attention that just ridicule, though. To a

great many people, this was a comment on German society. In the words of

the

National-Zeitung only two days after the incident "(t)he

boldest and most biting satirist could not make our vaulting militarism,

which 'o'erlaps itself and falls on the other side' the subject of a

satire which could stand comparison with this comic opera transferred

from the boards to real life /.../ Somebody's brains and somebody's

backbone have been lost; the honest finder is invited to hand them in at

the office of the Köpenick town-hall". [7) The Social Democratic

Vorwärts

found "(t)he chief actor in the farce /.../ much more intimately

acquainted with that mental attitude of the officials which has been

produced by militarism and by Prussian administrative practice than all

those questionable geniuses who have just been philosophizing in the

Conservative Press upon the specific Prussian spirit." [8] The "Köpenick

Caper" was considered by many to be the inevitable consequence of the

"rule of uniform" and it gave rise a number of acerbic comments. The

Berliner Tageblatt

summed up the feelings of a great number of Germans when they wrote

"(w)e talk of our civic pride, of manly courage before the thrones of

Kings, of the State based on law, and of our constitutionalism. It is a

strange commentary upon these and upon the rest of the fine phrases we

employ, but it is undoubtedly a fact that in Prussia the uniform

governs." [9]

On 26 October, Herr Voigt was arrested and later charged with

"unlawfully wearing uniform, with offending against public order, with

depriving subjetcs of their liberty, with fraud, and with forgery." [10]

At the trial, sympathies lay almost universally with the defendant.

Even the judge in the case the chief in summing up the case passed his

chief censure "upon the police system or expelling discharged prisoners

from places where they had settled down to a new life and to honest

work." [11] He then admitted several of the extenuating pleas which were

advanced by counsel for the defense, and, after having found Voigt

guilty on all counts of the indictment, sentenced him to four years'

imprisonment. Kaiser Wilhelm II, however, pardoned him on 16 August,

1908, and Voigt would go on capitalizing on his fame until he died in

1922.

The case gave rise to several books, songs and plays. There was simply

something irresistibly fascinating about the simplicity and sheer gall

of Wilhelm Voigt's exploit. Not only had he dared to camly impersonate a

Prussian officer; he had managed to do so in such a manner that it

never even occurred to the soldiers that he was not the genuine thing.

As The Times put it; "(f)rom his studies of the German officer at work

and at play this decrepit cobbler of nearly 60 years of age, with his

horny hands, his white hairs and his gaunt figure bowed by years of

penal servitude, was able to evolve a personage which passed for a

captain of the 1st Foot Guards." [12] And even if the comments on "the

rule of uniform" weren't entirely on the mark, in the general debate

following it was claimed that "the soldiers who took part in the raid

are understood to have been exonerated from all blame by their genuine

military superiors and to have been told that they acted quite

correctly. Some /.../ jurisconsults are indulging in speculations as to

what would have been the position of those ten soldiers if /.../ they

had shot down or bayoneted the unhappy Burgomaster of Köpenick. there

appears to be consensus of opinion that they could not have been held

legally responsible for their homicidal action." [13] As such, the

interpretation of the event at the time was as important as what had

actually transpired.

And poor Dr. Langerhans? Well, not suprisingly, he was overwhelmed by

the public ridicule and sent in his resignation a few days after the

incident. However, the citizens of Köpenick held a meeting at which they

passed a resolution of confidence in their Burgomaster and promised to

stand by him.

As a great writer once put it – all's well that ends well, isn't it?

Footnotes:

1. "The 'Captain Of Köpenick.'." Times [London, England] 3 Dec. 1906: 5. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012

2. Ibidem

3. Ibidem

4. "The Kopenick Raid." Times [London, England] 19 Oct. 1906: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012.

5. "The Köpenick Raid." Times [London, England] 20 Oct. 1906: 5. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012.

6. The National-Zeitung, as translated and referred in

The Times; "The Kopenick Raid." Times [London, England] 19 Oct. 1906:

3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012.

7. As translated and referred in The Times; "The Kopenick Raid." Times

[London, England] 19 Oct. 1906: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14

Oct. 2012.

8. As translated and referred in The Times; "The Kopenick Raid." Times

[London, England] 19 Oct. 1906: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14

Oct. 2012.

9. As translated and referred in The Times; "The Kopenick Raid." Times

[London, England] 19 Oct. 1906: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14

Oct. 2012.

10. The 'Captain Of Köpenick.'." Times [London, England] 3 Dec. 1906: 5. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012

11. Ibidem

12. "The 'Captain' Of Köpenick." Times [London, England] 30 Oct. 1906: 5. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012.

13. "The Köpenick Raid." Times [London, England] 22 Oct. 1906: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 14 Oct. 2012.